Historians usually trace the emergence of liberalism to England, France, and Germany, where in the early nineteenth century thinkers such as John Stuart Mill, François Guizot, and Wilhelm von Humboldt gave shape to a recognizable cluster of political ideas—but rarely to Italy. Yet in Carlo Cattaneo (1801–1869), Italy found a convincing and articulate spokesman for what we now consider a liberal worldview. Cattaneo expressed his liberalism most forcefully in his economic writings, which preoccupied him in the years leading up to 1848. He had turned to political economy as a young journalist in the 1830s, when he began writing for the progressive Annali universali di statistica. His mentor, the philosopher Gian Domenico Romagnosi, who was editing the journal at the time, encouraged him to read widely in the field. Cattaneo clearly followed Romagnosi’s advice. In the introduction to his treatise on Jewish Disabilities, written in 1836, he referred in just one paragraph to more than a dozen economic thinkers working in at least three different languages. But among all these worthy predecessors, two names in particular stand out in his published writings. Adam Smith, it seems fair to say, provided Cattaneo with his economic principles, while Jeremy Bentham showed him how to apply these principles to real world problems. Cattaneo once called Smith the “organizer and master” of economic science. Like Bentham, Cattaneo would use Smith’s principles—the universal benefits of free trade, the importance of capital for development, the salutary impact of cities on the countryside—to attack the vestiges of mercantilism and feudalism that he believed were hindering economic growth.

Cattaneo merits a place among the founders of early nineteenth-century liberalism because, like other liberals, he conceived of men and women as individuals rather than as members of corporate bodies. People, he argued, should freely pursue their own interests, especially economic interests, both because justice demanded it and because the pursuit of self-interest, when kept within reasonable bounds, was the best way for society to achieve prosperity and the rewards of civilization. Also like other liberals, he argued for the elimination of those encumbrances, the legacies of Europe’s feudal and mercantilist pasts, that made the pursuit of self-interest impossible: the vestiges of medieval corporations, restrictions on property rights, especially the right to buy and sell land, and the battery of mercantilist barriers to free trade, of which tariffs were simply the most visible. Applying these principles to his immediate surroundings, Cattaneo asked how prosperity could be brought to a regional economy such as the Lombard. His answer was clear: remove all barriers to economic activity so as to unleash the region’s human and natural potential. In arguing his case, Cattaneo made what was perhaps his most original contribution to contemporary economic debate. Rather than endorse the emerging nationalist discourse, often associated with the German economist Friedrich List, that posited the nation-state as the proper field for economic activity, he rejected notions of nationality based on ethnicity or race. “Manufactures,” he once said, with emphasis, “do not speak languages.” Instead, Cattaneo understood the state in purely political terms and sought to create the largest commercial field possible, which would spread the benefits of free trade across borders and among any number of political entities ranging from provinces, to states, to empires. Taken together, these liberal ideas received fullest expression in his early writings on tariffs, in his Interdizioni israelitiche, and in his long review of Friedrich List’s National System of Political Economy.

1

Cattaneo started writing for the Annali universali di statistica in the early 1830s. Most of his contributions were short notices of no more than a few pages, but two of his longer articles dealing with tariffs in the United States and Germany targeted mercantilism. For a Lombard like Cattaneo, the issue was certainly relevant. He had been born and raised in Milan, the provincial capital, and safeguarding Lombardy’s interests concerned him most as he contemplated the economic realities of post-Napoleonic Europe. In 1815, after the Congress of Vienna had restored Habsburg rule to northern Italy, control of the Lombard economy passed to Austrian policymakers, who set out in the 1820s and 1830s to integrate their Italian territories into a customs union that would remove the trade barriers between Lombardy and the Habsburg lands to the north, while subjecting the province to the Austrian regime of prohibitive tariffs on merchandise from abroad. Their goal was to encourage trade between Lombardy and the empire’s German provinces by creating an area of free exchange, and to foster the development of domestic production by imposing duties on imported manufactured goods. By the 1830s, however, Lombards began to question Austrian policy as they debated the future of their own economy. For many, the Habsburgs seemed all too ready to sacrifice Lombard interests for the sake of other parts of their empire.

The Nullification Crisis in the United States provided the occasion for Cattaneo’s first extended treatment of the tariff question in a long article on the “Questione delle tariffe daziarie negli Stati Uniti d’America,” which appeared in the Annali for March 1833. By the early 1830s, residents of South Carolina had come to blame their state’s depressed economy on the nation’s protective tariffs. The federal government had imposed tariffs starting at the end of the Napoleonic wars, most recently in 1828 and 1832. Their purpose was to encourage the development of American manufacturing, mostly in the north, and provide the federal government with a source of revenue. The connection between tariffs and South Carolina’s depressed economy may be questionable, but South Carolinians at the time were convinced it was real. To many, it seemed the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 had simply raised the price of consumer goods while depressing overseas demand for Southern cotton, all in the interest of protecting Northern manufacturing. In November 1832, in an act of defiance, they nullified the tariffs and threatened to secede from the Union should the federal government choose to enforce them. By March 1833, when the Annali published Cattaneo’s article, both sides had called up troops and the outcome of the dispute was far from certain. Cattaneo ended his article with the prediction that war might result if the tariffs were not removed.

In his analysis of the controversy, Cattaneo came out strongly against tariffs. The economic doctrine supporting them was specious, they depressed the price of exports, and they encouraged smuggling. The affect of the tariff of 1832, he wrote, was “to provoke ineluctable contraband, and to divert commerce from true and honorable ways to wrong and dark ways, with a contempt for the laws and an annihilation of public morals, and a ruinous disruption of all prices and of all production.” In opposing tariffs, Cattaneo came before the public as a proponent of free trade, a follower of Adam Smith and the British school of political economy. But his article was about more than just tariffs: it was about “Colbertism,” which was an issue, he said, of “supreme importance” for Europeans. What Cattaneo meant by “Colbertism” was clear enough. Jean Baptiste Colbert, finance minister to Louis XIV, had pursued policies that Adam Smith would later criticize in Book IV of the Wealth of Nations as the “mercantile system.” Mercantilist doctrine envisioned the state as an economic enterprise designed to accumulate wealth in the form of gold and silver. States without a natural supply of precious metals depended on international trade to fill their treasuries. They encouraged exports, because selling goods overseas brought gold and silver into the national economy, and they imposed tariffs to protect domestic industries and discourage imports. Tariffs also raised revenue that central governments could employ to finance improvements—roads, bridges, canals, harbors. Mercantilists thought in terms of large economies that would be self-sufficient and prioritized national considerations over local. In the seventeenth century, mercantilism in economics went hand in hand with raison d’état in politics. Both could be seen as stages on the road to state centralization.

When Cattaneo opposed Colbertism, he was objecting to more than just tariffs. He was also questioning an economic system that would sacrifice local interests for the supposed greater good of the nation. Neither tariffs nor improvements affected all regions equally, and regions that payed most in tariffs might receive least in improvements. As Cattaneo pointed out, the South in general exported more goods than the North and was therefore making a disproportionate contribution to the national treasury, a contribution that did not necessarily return to the region in the form of roads, bridges, or canals. The lesson would not have been lost on Italian readers. South Carolina formed a regional economy within a larger federation, just as Lombardy formed a provincial economy within a larger empire. Cattaneo, like the Nullifiers, believed that revenue raised locally should be spent locally. In a sympathetic report of President Jackson’s annual message to Congress in December 1832, Cattaneo endorsed limiting central government in order to safeguard local interests: “And here with unprecedented wisdom and moderation,” he wrote,

the president announced the hope that he nourished of reducing the government to that simple machine that the constitution wanted; such that the states might feel only the remote influence of a power that was satisfied to preserve internal and external peace, to ensure the uniformity of the monetary system, to maintain the sanctity of contracts, to spread enlightenment, and to discharge unheard a few other functions, not aiming to constrict human liberty, but to confirm the rights of man.

This endorsement of limited government aligned Cattaneo with American sectionalists in opposition to nationalists. In the United States, nationalists like John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay promoted tariffs on the grounds that they would be good for the nation as a whole, encouraging industrial development and providing the federal government with funds for undertaking public works necessary for national improvement. Sectionalists like John Calhoun opposed tariffs, arguing that they depressed South Carolina’s economy and were little more than a mechanism for funneling southern wealth to the North. By siding with South Carolina in the tariff dispute, by opting for free trade and limited government, Cattaneo took a stand against the nationalist position, foreshadowing his argument with Friedrich List a decade later.

Cattaneo, however, did not follow the sectionalists into a defense of slavery. During the Nullification Crisis, South Carolinians, dependent on a slave economy, had wanted to defy northern abolitionists, whose cause in the 1830s was beginning to gather momentum, as much as they had wanted to dismantle tariffs. Seen from within Cattaneo’s critique of Colbertism, slavery was an unfortunate consequence of mercantilism as European nations extended their trade networks into the Americas, and Cattaneo found it abhorrent. It was immoral—“the enslavement of man is ugly, dangerous, and fruitful of every misery”—and its impact on Southern slaveowners was harmful, regressive even: “the cohabitation with slaves, the brutal lust that springs from it, the easily preserved opulence, the habitual laziness, the blessed and haughty ignorance, the isolation from foreigners, whose conversation with the frightened negroes seems to be the torch of rebellion, had brought southerners all the more closely to the feudal type, or rather to the Asiatic….” Instead, Cattaneo demonstrated a marked preference for the economic vitality of the North, where the “sublime invention of the steam engine increased a hundred fold the navigation and the industry and the wealth and the culture and the self-confidence of the free citizens of New England.” The contrast he drew between the two systems could not have been starker, and Cattaneo concluded his attack on Colbertism with the suggestion that someday the North might eliminate tariffs and the South might abolish slavery: “it only stands to hope, then, that both fall together.”

Continuing his foray into political economy, Cattaneo turned next to the German customs union. At the end of the Napoleonic wars, the Congress of Vienna had reduced the number of German states to thirty nine and brought them together politically in a loose Germanic Confederation. In 1834, after a decade of negotiations, the majority of these states, with the notable exception of Austria, organized themselves economically into a Zollverein, or customs union. Historians usually interpret the Zollverein as a Prussian victory because it sidelined the Austrian economy. Cattaneo examined the question in a short article on the “Lega daziaria germanica” for the Annali in 1834. His subject, he said, was once again “Colbertism,” an affliction to which the German states were particularly susceptible. Under Napoleon, Cattaneo explained, the Continental System had protected German industry by prohibiting trade with Great Britain. With Napoleon’s defeat, however, the system collapsed, British goods flooded the market, and German manufacturing suffered. The German states responded by erecting customs barriers, each state isolating itself from the others, each hoping to protect its nascent industries. To the damage caused by unexpected British competition, Cattaneo remarked, now was added the damage caused by protection: “Germany under the scourge of false economy had become an immense field of customs agents and swindlers, who either fighting or clandestinely helping one another, forever conspired to devour a large portion of the common wealth, to depress agriculture, industry and honest commerce, and to sever the social bonds among the diverse members of the nation.” German statesmen eventually recognized their mistake and set the negotiations into motion that established the single customs union.

Once again, Cattaneo emerged from the discussion a champion of free trade and a critic of protectionism. The Zollverein, he argued, was a compromise solution that accepted Colbertism in regard to the world outside the union, but implemented free trade within it. This was a step in the right direction; and Cattaneo hoped that in the near future the benefits of free trade would be extended to an even greater geographical area. Most of the article was taken up with the story of the negotiations leading to the creation of the customs union, but Cattaneo ended with an observation that made clear what he meant by extending the benefits of free trade. The Zollverein had excluded Austria and the other territories of the Habsburg monarchy, including those in Italy. There was no reason, Cattaneo pointed out, why Austria, along with Lombardy and Venetia, the Tyrol and Illyria, could not be brought into conformity with the German union. The resulting competition would benefit everyone. He closed with a magnificent vision of an immense free-trade zone: the Italian provinces connected to Europe’s markets through its great river networks, trade from the Levant flowing through Venice on its way to northern Europe, the economic life of the Adriatic revitalized after three centuries of stagnation. As this vision demonstrates, Cattaneo reasoned about economics as an early nineteenth-century liberal, opposed to protection, desiring for Lombardy the largest field of free commercial activity possible, working within an international context that would link the German states, the Habsburg monarchy and its Italian territories. He was a liberal, but not a liberal nationalist. He did not press for tariffs to protect Italy’s nascent industries after the fashion of an American nationalist or an advocate of the German Zollverein.

2

Cattaneo’s next contribution to political economy, written in 1836, but not published until 1837 because of difficulties with the Austrian censor, continued his attack on the ancient régime. Known today simply as the Interdizioni israelitiche, the book explored the economic repercussions of the disabilities historically imposed on Europe’s Jews, especially the laws excluding them from landownership. The case that drew Cattaneo’s attention and became the starting point for his thinking involved two French Jews who were prevented from buying land in the Swiss canton of Basle-Country. The purchasers, two brothers with the surname Wahl, had inadvertently stumbled into a legal bind. They were French citizens, and according to a pair of treaties concluded in 1827 and 1828, French citizens had the legal right to purchase land in Switzerland. But they were also Jews, and the laws of Basle-Country barred Jews from owning land. When asked to resolve the contradiction, the canton’s Grand Council upheld local law and prohibited the purchase. Cattaneo’s reasons for writing about the affair, which became something of a cause célèbre, are not at all clear. But defending the Wahls provided him with the perfect opportunity for pursuing his campaign against those vestiges of Europe’s feudal past that he believed were violating the universal rights of private individuals. As he made his case, Cattaneo articulated a liberal vision stressing the convergence of justice and sound economic reasoning: “the progress of good economy,” he wrote, “is revealing little by little that toleration is only a most delicate sense of justice and social utility….”

Cattaneo defended the Wahls with a number of different arguments. As a matter of public right, the purchase should have been allowed to take place because the Wahls were undoubtedly French citizens and the treaties were legally binding. Authorities across Europe had long recognized that when two sets of laws contradicted one another, the most recently enacted always took priority. The treaties between France and Switzerland dated from only 1827 and 1828, whereas the banning of Jewish landownership stretched back for generations. Nor had Basle-Country ever objected to the treaties on the grounds that they contravened local law. On the contrary, the canton had accepted them without protest, tacitly acknowledging that they superseded the earlier prohibitions. As matter of private right, the canton’s decision to stop the purchase prevented the Wahls from engaging in activities necessary for their well-being and thereby amounted to a violation of the their civil liberties. Cattaneo always regarded men and women in their economic capacity as individuals who should be free to pursue their own interests. Whereas in the past, European governments had organized their populations in corporations—estates, municipalities, guilds, monastic orders, universities—that imposed restrictions on what they could and could not do, modern society was centered on private individuals. Cattaneo was convinced that when these individuals followed their interests, when they exercised their right to own and sell property, they worked for the greater good of all.

In making this case, Cattaneo formulated an argument that identified property as the very foundation of civilization. Property, he wrote, “is the first fundamental of commerce, and therefore it creates the division of labor, which is considered by all thinkers as the source of wealth. Without the faculty of exchange, everyone would need to prepare for himself all the things that he requires; there would be neither artisans nor arts; humankind would lie in the most abject nakedness and the most distressing savagery.” To place limits on property, Cattaneo continued, inevitably harmed the public good. “All mercantile or landed privileges, and all protective tariffs that under false pretenses limit the right of free exchange, are an infraction of the sacred right of property, and a profound wound to general prosperity.” This argument would have been familiar to any reader of contemporary political economy. Applied to the Wahls, its implications were clear. As individuals, regardless of their religion, the brothers had the right to own, use, and sell property in order to meet their needs. Any restriction on their access to land amounted to a violation of their rights and a blow to the well-being of society.

Moving his argument from theory to practice, Cattaneo pointed out that Basle-Country punished only itself when it prevented Jews from owning property. Land required investment to become productive. “Good agriculture,” he declared, “cannot exist without capital.” The canton was poor, it needed the Wahls’ money, and it deprived its agriculture of investment when it prohibited the brothers from buying their farm. Here was Cattaneo’s main point: the production of wealth was limited by the amount of available capital. It was an insight he had gained from Bentham, who had laid down the principle in his Manual of Political Economy (1793–1795). Bentham may not have published the Manual in his lifetime, but his French translator, Etienne Dumont, inserted its most important sections into the work he called Bentham’s Théorie des Peines et des Récompenses. Cattaneo owned the Brussels edition of Bentham’s Oeuvres (1829–1830), the second volume of which contained the treatise on punishments and rewards. Bentham’s principle was part of his campaign against mercantilism. Because capital limited trade, there was little governments could do to increase wealth. They might use import or export duties to shift capital from one sector to another, they might tax one sector to provide incentives for another, but moving capital in this way would never increase its quantity. A more effective policy would avoid prohibitions altogether and allow entrepreneurs to invest their capital wherever they thought it would perform best. This maxim lay at the center of Cattaneo’s political economy. He applied it to Lombardy, where generations of investment had turned a land of “sand and swamps” into the “richest countryside in the world.” He applied it to Ireland; and he applied it to the Habsburg monarchy, where local laws were preventing Jewish entrepreneurs from investing in capital-starved agriculture. Finally, in the case of the Wahls, he applied it to Switzerland, where restrictions on Jewish landownership had inflicted unnecessary harm on the country’s economy.

The need for investment prompted Cattaneo to follow Bentham and defend money lending. For Bentham, usury was not a crime, but rather a legitimate way of providing capital to those who required it, and government attempts to limit interest rates amounted to unwarranted and potentially damaging infringements on the freedom to make contracts. Financing ventures that carried substantial risks of failure naturally called for high rates of interest and businessmen should be free to set rates at appropriate levels. Bentham also pointed out that a willingness to take risks was a necessary precondition for social improvement since all great innovations were originally risky until repeated success demonstrated their viability and made them routine. Entrepreneurs who were prepared to borrow money at high interest rates in order to pursue novel undertakings were, for Bentham, the great promoters of civilization, and the world would have been a poorer place without them. The practice of usury, in fact, made such economic sense that only religious bigotry, which associated money lending with Jewish avarice, stood in the way of its acceptance. Cattaneo had clearly read Bentham’s Defense of Usury (1787)—it, too, was available in the Brussels edition of Bentham’s Oeuvres—and made similar arguments, attributing the antipathy toward money lending to the rise of Christianity in the late Roman Empire. He then drew the larger conclusion that in economic matters, considerations of race, ethnicity, religion or language should play no role whatsoever. Economies operated according to natural laws that were indifferent to human prejudice: “Do the francs of the Jews have perhaps a bad odor?” he asked rhetorically. “Will a vine planted by a Jew in a previously uncultivated field yield perhaps bitter or poisonous grapes? Nature does not take part in our blind resentments; she is a just and good mother to all hard-working men. We wage war on ourselves by censuring and opposing the desire of clement nature. Leave it to the Jew, and the industriousness that has amassed millions will know how to nourish the fecundity and pleasantness of the land.”

Religious bigotry, however, had taken its toll, and the consequences were profound. The prohibitions against landownership, Cattaneo noted, had driven Jews away from the least profitable sector of the economy, agriculture, and into the most profitable, commerce and finance. Successful in business, many Jews accumulated substantial fortunes, but rather than invest their wealth, which Cattaneo considered in the public interest, they reacted to their disabilities by hoarding it. As he pointed out, Jews were refused the right of inheritance, which persuaded them to conceal their wealth through money lending, and they were denied the amenities, rewards and privileges that would have encouraged them to assimilate and contribute to general society. These disabilities were considerable, as Cattaneo made clear. Jews were “excluded from mixed relationships, which does not happen to other sects: excluded therefore from intimate affections and from the community of things and of inheritance: excluded from funerary honors, from arms, from the magistracy, from liberal studies, from the free study of their own laws: excluded from the guilds and therefore from the exercise of the mechanical arts: they could not reside under a roof that welcomed Christians.” The effect of these exclusions was to isolate Jews from European society on all levels: Physically, by consigning them to ghettoes in “the most fetid part of the city.” Economically, by relegating them to “trading in scraps of cloth.” Socially, by prohibiting all relationships with Christians, given that “severe laws prevented Christians from eating at the same table, from playing cards, from conversing with them.” These exclusions were deeply rooted in the European past, a legacy of the feudal order that had assigned people to corporate bodies. One of Cattaneo’s purposes with the Interdizioni israelitiche was to demonstrate the impact of law on economic behavior, and in this case, he made it clear that the legal code barring Jews from the benefits of society had been profoundly damaging, encouraging them to accumulate wealth while removing it from general circulation.

As he weighed the profitability of different sectors of the economy, Cattaneo entered into a debate over the future of Lombardy that had preoccupied economists since the end of the Napoleonic occupation: should the province remain primarily agricultural or should it move toward industry? The question was important for progressives who were trying to decide how Lombardy should best participate in the forward movement of the age. Whereas some, like the businessman Giuseppe De Welz and the economist Melchiorre Gioia, argued for the primacy of industry and the use of protection to achieve it, Romagnosi called for the removal of all prohibitions, believing that free competition would allow the Lombard economy to develop spontaneously, without artificial restraints, and achieve a salutary balance between agriculture and industry. Romagnosi always preferred agriculture, considering it the fundamental source of wealth and social stability, and he wanted Lombardy to approach manufacturing naturally, so as to avoid the excesses often associated with English industrialization. Like Romagnosi, Cattaneo began with agriculture and argued for balance. The land required capital in order to become productive, he explained in the Interdizioni israeletiche. It needed to be cleared, drained, and improved by the application of science and technology. Historically this investment had come from cities, where businessmen were looking for opportunities to invest their excess profits. A healthy economy, then, required agriculture to feed its urban populations, as well as industry to supply its countryside with manufactured goods and capital.

The problem, however, lay in attracting this capital to the countryside, because investments in land, no matter how prestigious, always returned less, and historically far less, than investments in commerce, manufacturing, or finance. As he assessed the profitability of agriculture, Cattaneo warned his readers that he was not trying to disparage what many considered Lombardy’s great strength. He began with Adam Smith’s observation that because agriculture was unsuited for the division of labor, for the application of machinery, and as a field for invention, it was less susceptible to increases in productivity. What is more, land did not enjoy the flexibility of other assets. Whereas merchandise could be divided into smaller parcels and sent in different directions, from one market to another, in response to changes in demand, the land was fixed and could not be moved. Nor did landed wealth have the constancy usually attributed to it. Buildings decayed, neighborhoods changed character, trade routes were relocated, commercial centers rose and fell, states changed hands and imposed new commercial regulations—all of which depreciated the value of the land and added to the risk of ownership. Laws of entail and primogeniture only exacerbated matters by making it difficult for proprietors to sell their land before suffering losses. The list of liabilities went on, but Cattaneo’s point was clear enough: any businessman seeking profit would need to think twice before investing in land.

But political economy taught that only an increased flow of capital would improve agricultural productivity. If the promise of profit proved inadequate, then the incentive for investment had to be found elsewhere. Broadening his understanding of human motivation to include factors other than pecuniary gain, Cattaneo emphasized the social and moral considerations that drew successful businessmen to the countryside. Wealth derived from manufacturing or commerce, he observed, might increase rapidly, but it also required constant attention. Exhausted by incessant worry, businessmen who had achieved success were often ready to trade profit for the prestige and comfort that came with landownership. Attracting businessmen to the countryside became Cattaneo’s solution to the problem of agricultural productivity. “This inclination of industrialists to fix their wealth in the land,” Cattaneo asserted lyrically, “is the soul of agrarian life.”

The industrialist… erects generous buildings, fills plantations, goes in search of water for irrigation; in a word, through expenditure and care, he satiates the land, which can then express its innate vigor. In this way, the swamps of the Low Countries, the gravel sands of Milan, the meager hills of Lucca and of Florence and of the valley of the Rhine have become the most pleasurable and populous and civilized countries of the globe. It is the wealth of ancient industry that, concentrated on a grateful soil, rendered it so thick in prosperous villages and sumptuous cities.

Cattaneo then argued for the elimination of all those encumbrances and prohibitions that prevented successful businessmen from purchasing and investing in land. These included laws of entail and primogeniture, which obstructed the free sale and especially the free ownership of land, and they also included the religious disabilities that prevented wealthy Jews like the Wahls from residing in the Swiss countryside and enjoying the respect and prestige that accompanied landed existence.

Cattaneo’s vision for Europe’s future was inclusive, based on toleration for difference, and recognizing the irrelevance of religious affiliation for participation in civil society. His solution for the continent’s agricultural problem was also quite Benthamite. Law, Cattaneo had shown, by marginalizing Jews, had obstructed the flow of an important source of capital. Abolishing these laws would allow businessmen to decide where best to invest their capital: some attracted by profit might turn to commerce, manufacturing, or finance; others drawn by prestige and social recognition might turn to agriculture. Cattaneo thus argued for the removal of all restrictions on ownership, occupation, and residence—the complete elimination of all vestiges of Europe’s medieval corporations—in order to create a modern society in which Jews and Christians could contribute to the public good by pursuing their self-interest. As he pointed out in the book’s introduction, contemporary economic thinking had shown beyond a doubt that justice, toleration and public utility went hand in hand. At the center of this liberal vision was an understanding of society as a collection of private individuals, each enjoying identical rights, regardless of race, ethnicity, language or religion. This was an important claim, especially coming at a time when these factors were gaining recognition as the very constituents of nationality. Cattaneo would confront the nationalist dimension of economic theory when he reviewed Friedrich List’s National Economy for the Politecnico in 1844.

3

List published his National System of Political Economy in 1841. Friedrich Engels considered List’s book the most significant German contribution to contemporary economic debate—but quickly dismissed it as plagiarized bourgeois nonsense. Cattaneo took the book far more seriously because he and List were asking a similar question: how could a developing economy compete with a neighbor like Great Britain that was far more advanced? But if their questions were similar, their answers could not have been further apart. The opposing doctrines of protection and free trade provided the point of departure. List readily acknowledged that in a world of economic equals, free trade would benefit all. But given the world as it was, a collection of diverse states at various stages of economic development, free trade worked to the advantage of Britain alone, allowing it to dominate all rivals. In answer to the free traders, List opted for protection as the best way for young economies to muster their strength until they were advanced enough to compete with Britain on an even playing field. Cattaneo, however, was not convinced. He rejected protection, argued vigorously for the universal benefits of free trade, and in the process put forward a political economy that rejected the principle of nationality and stressed the importance of applying capital to develop a region’s nascent industries in a world of free and open competition.

List is known today as a protectionist. He argued in his National Economy that under nineteenth-century conditions, protection was the only way for a backward nation to develop its manufacturing base and become prosperous and civilized, independent and powerful. Tariffs, he said, were desirable for a number of reasons. They encouraged domestic industries, particularly young industries, by guaranteeing that investors would not lose their capital because foreign competitors undersold their products. They were necessary because the world was composed of different nations, all at different levels of industrialization, all in competition with one another. They were justifiable because other nations used them. Britain’s corn laws, for example: why should Germany allow the free import of British manufactured goods, which undermined German industry, when Britain did not allow the free import of German grain? But List also understood that tariffs had to be used judiciously. They would harm nations that were not yet ready for industrialization, depriving them of markets for their agricultural produce while closing off sources of manufactured goods. Tariffs were appropriate only for those nations that had all the necessary preconditions for industrialization, but were confronting a more advanced competitor that was obstructing the development of their industries. Germany and the United States, for example, had an improved agriculture, ample raw materials, large populations, sufficient technical expertise and political stability, but were suffering under British competition. They could impose tariffs without harm because they no longer needed to exchange their agricultural products for British manufactured goods. Finally, List argued that protection was a temporary condition. Nations should adjust their tariffs according to the developmental levels of the various branches of their economies. Once a nation was fully industrialized, then it could drop its tariffs altogether and compete on the open market.

In his review of List’s book, Cattaneo rejected protection out of hand, opting instead for the most extensive freedom of trade possible so the demand of a huge market, encompassing many nations, both big and small, could stimulate industry everywhere. A large commercial field, he maintained, encouraged the division of labor, which led to specialization and increased productivity. Not all lands and peoples were suited for all industries. Free trade would allow each nation to concentrate on what it did best. “If Geneva,” he argued, “can produce watches for all human kind, and Lyon the most splendid silks, and Bohemia crystal, and England machinery and steel, then it is not worth the price to subvert this natural state of affairs, and this productive division of labor, in order to transform the Lyonnais into watchmakers and the Genevans into sorters of silk.” Cattaneo’s argument had significant implications for small states like Lombardy. Rather than attempt the impossible and develop all industries behind a wall of protective tariffs, the Lombards should concentrate on those trades for which they were best suited and rely on the international market to stimulate demand. “Only in this free competition,” he concluded, “can the smallest state enjoy the same vastness of field that the largest state enjoys. Whoever opposes to foreign industry a protective duty, wields a double-edged sword, and no one can say whether he does more harm to himself or to the other.—The enclosure that stops the passage of foreign industry, also stops that of national industry; and in the final account, when all space is enclosed, that prisoner who has the most narrow enclosure is the worst off and lives the most languid life.”

In arguing against protection, Cattaneo cited his favorite maxim—that industry is limited by capital—sometimes attributing it to Smith, sometimes to Bentham. In a closed world of protection, he pointed out, a young nation had only its own limited resources to draw on; but in a world of open borders and free trade, capital flowed easily and could be collected from many sources. In a long digression, Cattaneo demonstrated how British capital had built North America. Whereas List saw protection as the only way to develop American manufacturing, Cattaneo stressed the need for investment, which would come most easily under a regime of free trade. Whereas List attributed the commercial crises that periodically afflicted the United States to free trade, to a disparity between imports and exports, Cattaneo explained them by a shortage of capital. America, Cattaneo pointed out, was a new land and to develop it, to build its farms and cities, its roads, bridges and canals, to supply its farms with livestock and its stores with merchandise, required vast quantities of investment. Whether this capital was American or British made absolutely no difference. “Whence comes, then, the wealth of things that the planter brings to this new country?” Cattaneo asked. “The planter is not rich; he wants to become rich, no matter how laborious and unpleasant his life might be; he draws credit therefore from the local bank, which has been cobbled together by other adventurers, also rushing after a quick fortune. The local bank draws credit from another more distant; and in this way, from bank to bank, the staircase is ascended that joins agriculture to capital, or rather to the surplus that English commerce stores up, and branches out, with the intermediary of the American banks, to the remote planters and to the emergent cities.”

For Cattaneo, then, there was far more to economic growth than just trade. By focussing on tariffs and failing to take investment into account, List had missed the most important point. He had spent time in America, Cattaneo marveled, he had witnessed its tremendous growth, “but in the middle of this vast creation, he did not want to consider anything other than the interest of the American people in wearing socks and hats made in Boston rather than in Manchester at a lower price!” What is more, List had drawn the mistaken conclusion that American openness to British trade had merely resulted in a debilitating indebtedness to British banks and a vulnerability to British commercial crises. For Cattaneo, this indebtedness was not a bad thing at all, but rather a necessary condition for growth. No country, and especially no country with a young economy like the American—or, for that matter, with a small economy like the Lombard or the Swiss—could develop in isolation. They were too dependent on foreign investment. “What would America be,” Cattaneo asked rhetorically, “if it had not fallen into debt, and vastly into debt, to England? It was with the constant supply of English capital that it grew in a hundred years from a desolate and obscure colony to a leading nation.”

Cattaneo also turned to his advantage the two European examples that List had used to support his case for protection: Napoleon’s Continental System and the German Zollverein. The Continental System, List argued, had brought prosperity to France and all the countries included within the blockade, while the Zollverein did the same for the German states after Napoleon’s defeat. Cattaneo agreed with List that the two arrangements had benefited all involved, but he did not attribute their success to protection. What made the Continental System and the German Zollverein economically successful was not the protection they afforded to French or German industry, but rather the way they eliminated internal barriers and created a large French or German free trade zone. “Where the continental system was advantageous, it was not so because of the obstacles that it erected, but because of those that it abolished.… And the Germanic Customs Union, beneficent and wise, operates in a similar manner, not because it obstructs foreign trade with more solid customs borders, but because it expands the common field for German industry by sweeping away internal borders.” Here Cattaneo repeated the argument that he had made a decade earlier when he had written on the Zollverein for the Annali universali di statistica in 1834.“The more the customs borders are abolished, the more the marketing field is enlarged, the more industry will draw vigor and boldness from the two master principles of the division of labor and free emulation.”

Not only was List known as a champion of protection, but he was a German nationalist as well. He envisioned a world of independent nation-states that would be large and prosperous with well proportioned economies, balancing agriculture, manufacturing, and commerce in perfect harmony. These states would be linguistically and ethnically pure. He referred to them at times as “perfect nations.” This definition had several important consequences: perfect nations must have large populations and territories—List considered small nations “cripples”—they must have access to the sea, and they must have natural borders—coastlines, rivers, mountains—capable of providing for defense. List envisioned that small states would amalgamate to form large ones: a unified Germany would contain Denmark and Holland, for example, Belgium would join France, Canada and the United States would unite. Great Britain was the closest thing to a perfect nation that List had seen; and in his National System of Political Economy he put forward a program that would enable a unified Germany to reach a level of economic development that would make it a rival to Britain.

According to List political economy, properly understood, began with the nation. It asked how a “given nation can obtain (under the existing conditions of the world) prosperity, civilization, and power, by means of agriculture, industry, and commerce.” Other political economists—François Quesnay, Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, Sismondi—had dealt with the whole human race, a cosmopolitan approach that List considered mistaken because it did not reflect reality. The world according to List was made up of distinct nations, which competed with one another, and true political economy needed to acknowledge this fact. It needed to ask how an individual nation could prosper in a competitive field, instead of pretending that the world was one large community, consisting of all humankind, living in universal peace. Cattaneo disagreed, and his response to List rejected the nationalist approach. To begin with, Cattaneo never championed racial or ethnic purity, pointing out the advantages of combinations of all kinds. Scottish lowlanders, “mixtures of various continental races,” were stronger than the more racially pure highlanders. Persians, “mixtures of Georgian and Circassian blood,” were more “beautiful and robust” than the Parsees, who kept “themselves segregated from other nations.” One of the great advantages of trade in general was that it encouraged the intermingling of races and ethnicities for the benefit of all. “Trade mobilizes and mixes races, insinuating the habits of intelligence into those who were for centuries ignorant and sluggish,” he pointed out in his review. “This blending explains in part the productivity of the industrious cities of the Middle Ages, and the attractiveness and vigor of people in the United States.”

The persistent intermingling of peoples meant that List’s perfect nations—large, unified, homogeneous—simply did not exist, and most likely never would. Europe, and the world, were too messy. Cattaneo questioned List’s basic concept of the ethnically and linguistically uniform nation on the grounds that it totally ignored the current state of things. What is more, creating these perfect nations would entail reorganizing entire continents: “Belgium, Holland, and Denmark are for him future appendages of the German League…; Canada must join with the United States; Portugal with Spain.” To complicate matters even further, Cattaneo pointed out that many contemporary states were too small to count as perfect nations: “But if Holland and Portugal do not rank as nations, will Switzerland, Greece and Egypt, with equal or smaller populations…?” Nor would multinational empires, which lacked homogeneity, meet List’s standard: “Likewise, all those empires that contain more nations and more languages, above all the British Empire, but Russia, Austria and Turkey as well, would not rank as perfect nations according his doctrine.” In essence, List’s theorizing was based on a concept of nationality that had no bearing on reality: “And so, in substance, he wants to translate the idea of nation into that of state, or to expect that the course of centuries will have made the borders of states and those of languages everywhere coincide. And in that case, the doctrine of Signor List falls into the realm of utopias, that is of those designs that are totally disconnected from real conditions of time and of place.” List was a utopian dreamer, whereas Cattaneo was a realist intent on dealing with the world as it was: “We need a science that guides us now, and draws from the conditions of present states the rules of a possible and close future.” Thus Cattaneo had an empirical appreciation for the way things actually were, rather than an abstract plan for how they should be. Theories, he said, must deal with the real world, rather than assume the world could be reshaped in conformity with some abstraction.

To construct a system of political economy, then, on the basis of perfect nations amounted to pure fantasy. The building blocks of an economic order should reflect reality, taking into account the wide range of actual states, which could be as large as continents or as small as regions. There was no need to redraw the map of Europe in order to make it align with an abstract conception that contradicted common sense. As an advocate of free trade, Cattaneo dismissed the principle of nationality and contemplated an open commercial field that would extend across Europe and easily transcend existing borders, “since manufactures do not speak languages.” A European free trade zone would be advantageous for all and would easily out-compete Great Britain. “Would not the continent,” he asked, “in comparison to England, have some advantage of its own?” England, after all, possessed no unique foundation for its industrial supremacy and the continent could achieve what England had, if only free trade were allowed to unleash its latent productive forces. It was protection that was condemning Europe to backwardness. “No one will say that British opulence, however huge, should surpass that which is already accumulated or could in a short time be accumulated in both hemispheres. The population of the continent is ten times that of England, and when it is furnished with machines and roads and canals and grand associations, and develops in a free field the maximum division and the most opportune distribution of labor, according to the aptitudes of peoples and places, then it could do in one year the work that England does in ten; and could place each year in store a proportionate mass of capital.” So, whereas List argued for protection and prioritized the individual nation-state, Cattaneo embraced free trade as the way to bring progress to an entire continent. Whereas List’s approach was narrowly nationalistic, Cattaneo’s was broadly internationalist.

Cattaneo was writing from the perspective of a small European region, a circumstance that helps explain his reaction to List’s system of national economy. He accepted the political map of Europe as it then was: Lombardy and Venetia joined together, provinces within the Habsburg monarchy. He did not endorse List’s nationalism, which would divide Europe into several large “perfect nations,” each protected by a wall of tariffs, because in this mercantilist world, Lombardy would disappear within a unified Italy, one region among many, without any guarantee that its needs would be met. One problem with mercantilism was that policymakers at the center were always prepared to sacrifice local interests for what they considered the good of the state as a whole. This had been true in Jacksonian America, as Cattaneo demonstrated in his article on the Nullification Crisis, in which he distanced himself from the nationalist position, despite his abhorrence of slavery, on the grounds that tariffs promoted the interests of the North at the expense of the South. It was true of economic policy within the Habsburg monarchy, and it almost certainly would be true in any future Italian state founded on mercantilist principles. Free trade, on the other hand, in addition to providing the wide market necessary for industrial growth, restored incentive to local business interests and secured the greatest liberty for all. The lesson for Lombardy was clear: since the small region would never retain its autonomy in a world of economic protection such as List was proposing, it should become part of the largest free trade zone possible. This was the outcome he had recommended in his article on the Zollverein, in which he had suggested that Austria, along with Lombardy and Venetia, might join the German customs union, creating an immense free-trade zone connecting the Italian provinces to Europe’s markets.

Despite their substantial differences, Cattaneo and List did agree on one important point: that a well-developed economy must balance agriculture with manufacturing. “What he [List] says about the beneficial influence of industry on land ownership is the most praiseworthy part of the book; and we would like it to be well understood by those many, who repeating to satiety that we are an agricultural people, do not think that our lands owe three quarters of their value to the capital which industry of bygone centuries has deposited there….” The relationship between town and country had figured in the Interdizioni israelitiche, and Cattaneo spent the first part of his review of List’s book developing it even further. In answer to those economists who argued that Lombardy should focus exclusively on agriculture, Cattaneo advocated a well-balanced economy, explicitly citing Book III of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, “How the Commerce of the Towns contributed to the Improvement of the Country,” in order to make his case. His vision, articulated here as well as in his earlier writings on political economy, was thus forward looking in its acceptance of manufacturing as the force that would propel Lombardy into the modern age.

Industry, Cattaneo observed, often brought prosperity and civilization to agricultural regions that would have been unproductive and benighted without it. Farming communities never took full advantage of the land’s resources, often survived at subsistence levels, did little to encourage new ventures, and tended toward intellectual backwardness. Cattaneo described their sorry state in a passage that matched Marx’s strictures on the idiocy of rural life:

Scattered in secluded villas, farmers ask for little from each other because they all have the same needs and the same means for meeting them, and cannot exchange thoughts or things. They expect more from rude nature than from their fellows; they do not exercise their minds, because in rustic families they have not seen for centuries new contrivances or unusual clothing. Imitating what has always been done, not suspecting that one could do otherwise, and always wandering within a circle of persons and things, they pass from cradle to grave, without seeing an example of industriousness crowned with success, without emulation, without hope, resigned to the blind course of the elements, priding themselves on enduring discomforts, and scorning almost as weaknesses the pleasures they cannot have.

The introduction of manufacturing, however, had the potential to reverse this bleak situation by deriving wealth from resources that farming ignored, increasing the demand for a wide range of agricultural products, encouraging the application of advanced farming techniques, and attracting enterprising farmers to uncultivated regions where new industries were locating.

Cattaneo’s political economy was thus embedded in his overall conception of progress. He rejected the lingering Colbertism of the ancien régime and the neo-mercantilism of the new nationalism because he believed an economy based on the liberal principles of free trade and the individual right to own property would be more conducive to Lombardy’s prosperity. The expansion of industry would not only increase the wealth of the countryside, but it would bring political and intellectual enlightenment to rural areas that had previously known neither. A concern for good government, for justice and liberty, he pointed out, had historically originated within cities, among the entrepreneurial classes, and had spread from there to the countryside. From time immemorial, cities had served as the seat of knowledge and learning, of arts and sciences, of culture and civility. The intermingling of urban businessmen and rural landowners would therefore extend to the nation’s most backward regions the political and intellectual benefits that came with civil society.

© Timothy Lang | Bainbridge Island, Washington

A footnoted version of this essay can be downloaded here: Cattaneo’s Liberalism

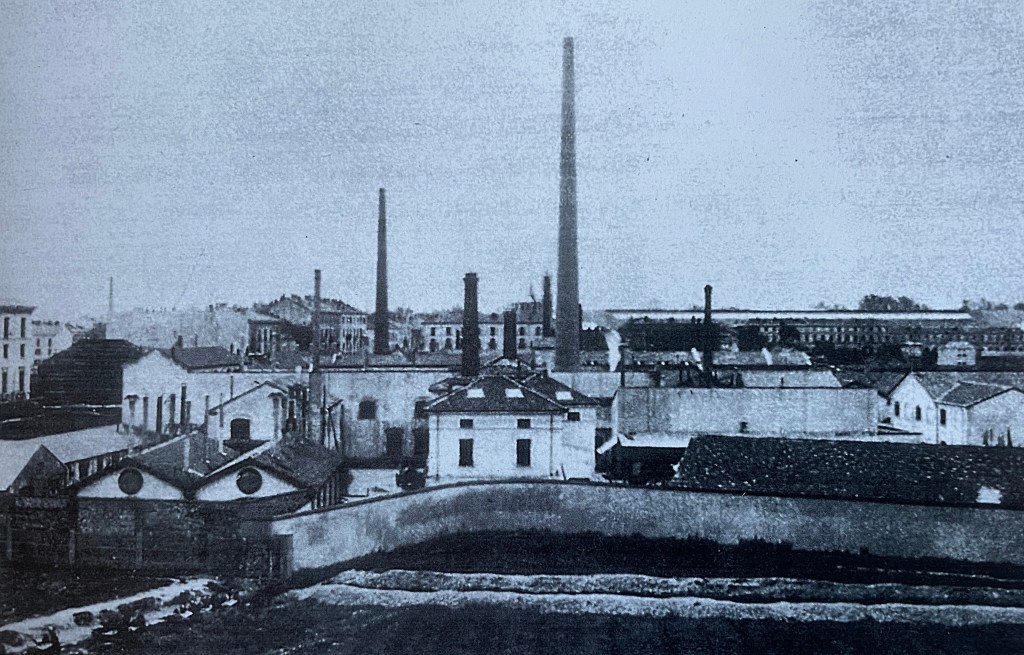

Picture credit: Pirelli rubber works, late nineteenth century, Bicocca district, Milan. Francesco Ogliari, Come eravamo: Milano e la sua provincia nell’Ottocento (Pavia: Edizioni Selecta, 2002), 149. Pirelli, which sourced its raw rubber from Asia and marketed its finished goods throughout Europe, represents what Cattaneo meant when he said that “manufacturing speaks no language.” Pirelli built its first factory in Milan in 1873, and by the early twentieth century had established branches in Spain, England, and Argentina.